I am no body like a house is not a home, 2019

10 × 4.4 m cotton fabric, of which 220 × 160 cm stretched and painted with gouache and oil

I am no body like a house is not a home, 2019

Metal, 2.1 × 2.1 × 3.4 m

Ich weiß nicht was ich mit meinen Händen machen soll, 2017

Mixed media on cotton, 220 × 140 cm

Untitled, 2018

Oil on carpet, 350 × 230 cm

Exhibition view Ein Leben bekommen, Pavillon 17, AdbK Nürnberg, 2019

Exhibition view Ein Leben bekommen, Pavillon 17, AdbK Nürnberg, 2019

Bett unter dem Tisch, 2019

Clay relief and headlamp, 20 × 27 cm

Wenn/weil ich groß bin, 2019

Clay and wood, approx. 70 cm

Untitled, 2019

Primer and pigment on cotton, 50 × 40 cm

Absorbing an eruptive flux, 2019

Mixed media on cotton, 70 × 100 cm

Coiling,

Ausstellungshalle, AdbK Nürnberg, 2020

Ein Leben bekommen,

Pavillon 17, AdbK Nürnberg, 2019

A Tooth for an Eye,

Regionale 19, Kunsthalle Basel, 2018

Ein Leben bekommen,

Pavillon 17, AdbK Nürnberg, 2019

Getting a Life

Simone Körner

Yet, the moment after, if the door was opened, spread about the floor, hung upon the walls, pendant from the ceiling—what? My hands were empty.*

Virginia Woolf, Haunted House

The floor becomes canvas. The linen pours out of the picture and begins to flow. The fluid bundles up, it squirts, to then continue its stretch across the space. That’s the first thing I noticed when entering Mirjam’s installation of Ein Leben bekommen [Getting a Life]. Nothing here is still, everything is in motion. A red, sprinkling nipple gets squeezed towards me by a gloved hand of the same color. The figure, 3.5 meters high, is bulging and heavy, its double chin swelling heavily across the chest, a pain I’m practically starting to feel myself. The carpet skin seems hardly inhabitable. Its owner looks down at me, their quiet mouth twisted into a laugh, and it’s just pouring out of their eyes. Many ambivalences that come with being the bearer of a bosom, become palpable here, since all too often the bosom is the object of societal notions on womanhood. Nevertheless, I don’t sense tragedy when I look around, after all, the figure’s look upon itself seems quite comedic. It doesn’t take its sorrow too seriously.

I move along and pass a metal frame, mapping out the dimensions of the artist’s living space. Underneath, a seemingly never-ending canvas billowing out from within itself, across the floor. It passes by a self portrait of the artist, attracted by the yellow light shimmering towards me from the last of the three rooms. On my way there I pause, smilingly, at a huge pair of shoes. These shoes are not made for walking, they invite you to stumble: already shattered at the tips, clunky and far too big for any foot. They’re made of clay and were constructed in the same way as the two high vessels also present in this exhibition. Almost archaeologically, they blend into the fragility of Mirjam’s landscapes.

Landscapes that keep reminding me of Virginia Woolf’s short stories. Each one can stand alone, and yet they all intertwine. The thoughts that I find here, bubble up and jump around from one place to the next, they are associative and describe worlds of subjective experience. A throwback, over and over again, to the conflict of being your own body, in a society convinced to know what that means and therefore compulsively trying to categorize it. In these rooms there’s no acceptance for whatever is supposed to put a description on this very form of being yourself.

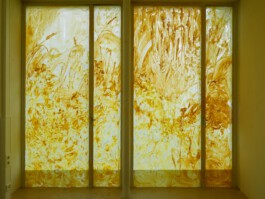

Neither for one’s own gender, nor for what it means here to get a life. One’s own privileges seem incredibly inappropriate. Moving on. I am now in the smallest of the three rooms. Crop spikes are painted onto the window, which gives the incoming autumn light an even warmer tinge and floods the whole room in yellow. The light shines onto my personal favorite: two hands grasping nothingness, touching at the palms. Their point of contact forms an anus. The background is blue.

My hands were empty. […] A moment later the light had faded. Out in the garden then? But the trees spun darkness for a wandering beam of sun. So fine, so rare, coolly sunk beneath the surface the beam I sought always burned behind the glass. Death was the glass; death was between us […]**

Mirjam’s works vomit, explode, tear and spit. The artist humorously fills up the spaces that she works in with fragilities and her own inadequacies.

It’s not about a fragmentation of the Self in the world, but rather about an expansion that brings to light one’s own vacuum. The bodies I see speak of synchronicity, of a volatility that cannot be pinned down. They’re lustfully sluggish, playfully sad and cozily desperate. They don’t want to be, they are, and in doing so they raise questions: What does it actually mean to be alive? How do we want to inhabit our corporeality? How can you even formulate a yearning for life beyond your own fixed body? How do we deal with getting a life?

* Virginia Woolf: Die Dame im Spiegel und andere Erzählungen, 1. Auflage. Frankfurt am Main: FischerTaschenbuch Verlag, 1978. S. 10. [“The Lady In the Looking Glass, And Other Tales”, 1st edition. Fischer Paperback Publisher, Frankfurt, 1978, p. 10.]

** Ibid.